[Home page] [General topics, Sources] [Army, Army Air Force] [Navy, Naval Air Force] [Eugen Pinak: contacts, publications] [Jeff Donahoo’s IJN Data Base] [Hiroshi Nishida's IJN Data Base]

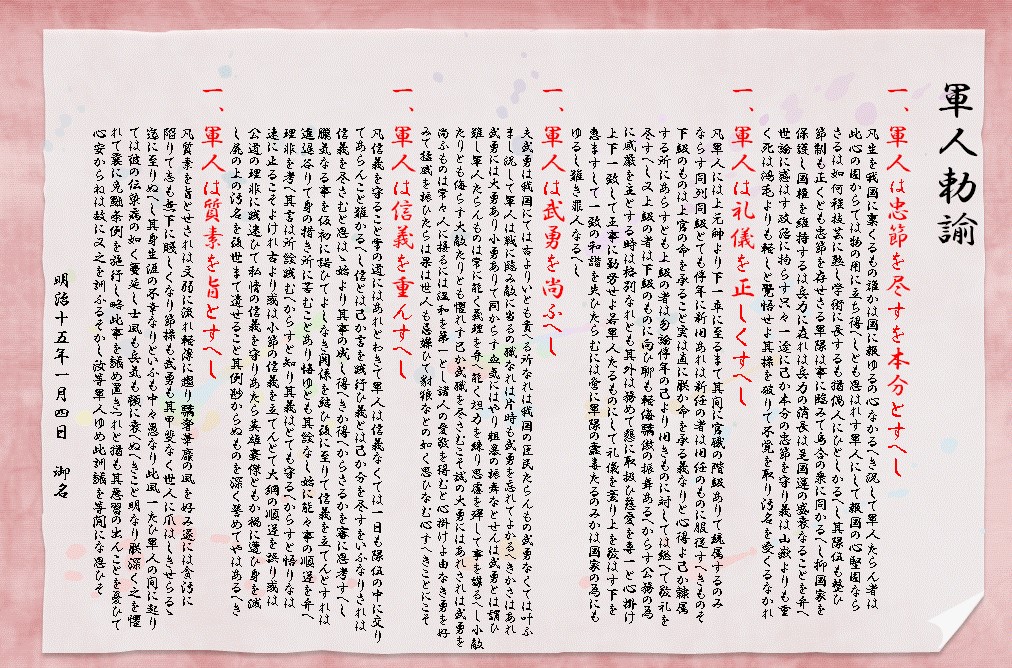

The Imperial Rescript to Soldiers and Sailors (軍人勅諭 =

Gunjin Chokuyu) was the official code of ethics for the Japanese military

personnel from its publication in 1882 until 1948, when it was officially

denounced.

All 2700 kanjis of the Imperial Rescript was to be

memorized by every IJA member, despite being written in a peculiar "Court"

Japanese language (by contrast IJN required learning, not memorization, of the

Imperial Rescript).

Importance of this document in moral education of

Japanese military was such, that a song was composed about it:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dAXssvglBgM

A good introduction to the history of the Imperial

Rescript can be found here: https://www.warrelics.eu/forum/japanese-militaria/imperial-rescript-soldiers-sailors-687558/

Eugen Pinak

F

IMPERIAL RESCRIPT

TO SOLDIERS AND SAILORS

The forces of Our Empire are in all ages

under the command of the Emperor. It is more than twenty-five centuries since

the Emperor Jimmu, leading in person the soldiers of the Otomo and Minonobe'

clans, subjugated the unruly tribes of the land and ascended the Imperial Throne

to rule over the whole country. During this period the military system has

undergone frequent changes in accordance with those in the state of society. In

ancient times the rule was that the Emperor should take personal command of the

forces; and although the military authority was sometimes delegated to the

Empress or to the Prince Imperial, it was scarcely ever entrusted to a subject.

In the Middle Ages, when the civil and military institutions were framed after

the Chinese model, the Six Guards were founded, the Right and Left Horse Bureaus

established, and other organizations, such as that of the Coast Guards, created.

The military system was thus completed, but habituated to a prolonged state of

peace, the Imperial Court gradually lost its administrative vigour; in course of

time soldiers and farmers became distinct classes, and the early conscription

system was replaced by an organization of volunteers, which finally produced the

military class. The military power passed over entirely to the leaders of this

class; through disturbances in the Empire the political power also fell into

their hands; and for about seven centuries the military families held sway.

Although these results followed from changes in the state of society and were

deeply to be deplored, since they were contrary to the fundamental character of

Our Empire and to the law of Our Imperial Ancestors.

Later on, in the eras of Kokwa and Kaei,

the decline of the Tokugawa Shogunate and the new aspect of foreign relations

even threatened to impair our national dignity, causing no small anxiety to Our

August Grandfather, the Emperor Ninko, and Our August Father, the Emperor Komei,

a fact which We recall with awe and gratitude. When in youth We succeeded to the

Imperial Throne, the Shogun returned into Our hands the administrative power,

and all the feudal lords their fiefs; thus, in a few years, Our entire realm was

unified and the ancient regime restored. Due as this was to the meritorious

services of Our loyal officers and wise councilors, civil and military, and to

the abiding influence of Our Ancestors' benevolence towards the people, yet it

must also be attributed to Our subjects' true sense of loyalty and their

conviction of the importance of "Great Righteousness." In consideration of these

things, being desirous of reconstructing Our military system and enhancing the

glory of Our Empire, We have in the course of the last fifteen years established

the present system of the Army and Navy. The supreme command of Our forces is in

Our hands, and although We may entrust subordinate commands to Our subjects, yet

the ultimate authority We Ourself shall hold and never delegate to any subject.

It is Our will that this principle be carefully handed down to posterity and

that the Emperor always remain the supreme civil and military power, so that the

disgrace of the middle and succeeding ages may never be repeated.

Soldiers and Sailors, We are your

supreme Commander-in-Chief. Our relations with you will be most intimate when We

rely upon you as Our limbs and you look up to Us as your head. Whether We are

able to guard the Empire, and so prove Ourself worthy of heaven's blessing and

repay the benevolence of Our Ancestors depends upon the faithful discharge of

your duties as soldiers and sailors. If the majesty and power of Our Empire be

impaired, do you share with Us the sorrow; if the glory of Our arms shine

resplendent, We will share with you the honour. If you all do your duty, and

being one with Us in spirit do your utmost for the protection of the State, Our

people will long enjoy the blessings of peace, and the might and dignity of Our

Empire will shine in the world. As We thus expect much of you, Soldiers and

Sailors, We give you the following precepts:-

(1)

The soldier and the sailor should consider loyalty their

essential duty.

Who that is born in this land can be

wanting in the spirit of grateful service to it? No soldier or sailor,

especially, can be considered efficient unless this spirit be strong within him.

A soldier or a sailor in whom this spirit is not strong, however well ordered

and disciplined it may be, is in an emergency no better than a rabble. Remember

that, as the protection of the State and the maintenance of its power depend

upon the strength of its arms, the growth or decline of this strength must

affect the nation's destiny for good or for evil; therefore neither be led

astray by current opinions nor meddle in politics, but with single heart fulfil

your essential duty of loyalty, and bear in mind that duty is weightier than a

mountain, while death is lighter than a feather. Never by failing in moral

principle fall into disgrace and bring dishonour upon your name.

(2)

The soldier and the sailor should be strict in observing

propriety.

Soldiers and sailors are organized in

grades, from the Marshal and the Admiral of the Fleet down to the private

soldier or ordinary seamen; and even within the same rank and grade there are

differences in seniority of service according to which juniors should submit to

their seniors. Inferiors should regard the orders of their superiors as issuing

directly from Us. Always pay due respect not only to your superiors but also to

your seniors, even though not serving under them. On the other hand, superiors

should never treat their inferiors with contempt or arrogance. Except when

official duty requires them to be strict and severe, superiors should treat

their inferiors with consideration, making kindness their chief aim, so that all

grades may unite in their service to the Emperor. If you, Soldiers and Sailors,

neglect to observe propriety,

(3)

The soldier and the sailor should esteem valour.

Ever since the ancient times valour has

in our country been held in high esteem, and without it Our subjects would be

unworthy of their name. How, then, may the soldier and the sailor, whose

profession it is to confront the enemy in battle, forget even for one instant to

be valiant? But there is true valour and false. To be incited by mere

impetuosity to violent action cannot be called true valour. The soldier and the

sailor should have sound discrimination of right and wrong, cultivate

self-possession, and form their plans with deliberation. Never to despise an

inferior enemy or fear a superior, but to do one's duty as soldier or

sailor - this is true valour. Those who thus appreciate true valour should in

their daily intercourse set gentleness first and aim to win the love and esteem

of others. If you affect valour and act with violence, the world will in the end

detest you and look upon you as wild beasts. Of this you should take heed.

(4)

The soldier and the sailor should highly value

faithfulness and righteousness.

Faithfulness and righteousness are the

ordinary duties of man, but the soldier and the sailor, in particular, cannot be

without them and remain in the ranks even for a day. Faithfulness implies the

keeping of one's word, and righteousness the fulfillment of one's duty. If then

you wish to be faithful and righteous in anything, you must carefully consider

at the outset whether you can accomplish it or not. If you thoughtlessly agree

to do something that is vague in its nature and bind yourself to unwise

obligations, and then try to prove yourself faithful and righteous, you may find

yourself in great straights from which there is no escape. In such cases your

regrets will be of no avail, hence you

(5)

The soldier and the sailor should make simplicity their

aim.

If they do not make simplicity your aim,

you will become effeminate and frivolous and acquire fondness for luxurious and

extravagant ways; you will finally grow selfish and sordid and sink to the last

degree of baseness, so that neither loyalty nor valour will avail to save you

from the contempt of the world. It is not too much to say that you will thus

fall into a life-long misfortune. If such an evil once makes its appearance

among soldiers and sailors, it will certainly spread like an epidemic, and

martial spirit and morale will instantly decline. Although, being greatly

concerned on this point, We lately issued this Disciplinary Regulations and

warned you against this evil, nevertheless, being harassed with anxiety lest it

should break out, We hereby reiterate Our warning. Never do you, Soldiers and

Sailors, make light of this injunction.

These five articles should not be

disregarded even for a moment by soldiers and sailors. Now for putting them into

practice, the all important is sincerity. These five articles are the soul of

Our soldiers and sailors, and sincerity is the soul of these articles. If the

heart be not sincere, words and deeds, however good, are all mere outward show

can avail nothing. If only the heart be sincere, anything can be accomplished.

Moreover, these five articles are the Grand Way of heaven and Earth and the

universal law of humanity, easy to observe and to practice. If you, Soldiers and

Sailors, in obedience to and to fulfil your duty of grateful service to the

country, it will be a source of joy, not to Ourself alone, but to all people of

Japan.

The 4th day of the 1st month of the 15th

Year of Meiji.

(Imperial Seal)

All rights reserved/Copyright© Eugen Pinak, unless otherwise noted.